[THIS IS SAMPLE TEXT FROM FIBERSHED.COM, PLEASE REMOVE & CREATE ORIGINAL CONTENT – QUOTING FROM & LINKING TO FIBERSHED.COM IS ENCOURAGED IF YOU WISH TO SHARE CONTENT]

Translating the color of sea and sky to our clothing has required the use of synthetic compounds created from fossil fuel derived substances at industrial scales of production. Growing your color is an alternative to this system that engages and reconnects us with the land, its seasons and processes. We see that cultivating your own form of blue is now returning to our textile culture as interest grows from gardeners, farmers, designers and makers across the world. There are many species grown, and yet it is Persicaria tinctoria (syn. Polygonum tinctorium)—Japanese indigo—that has can be easily cultivated in many parts of North America (including our fibershed in Northern CA), and other temperate climates.

(Photo by Paige Green)

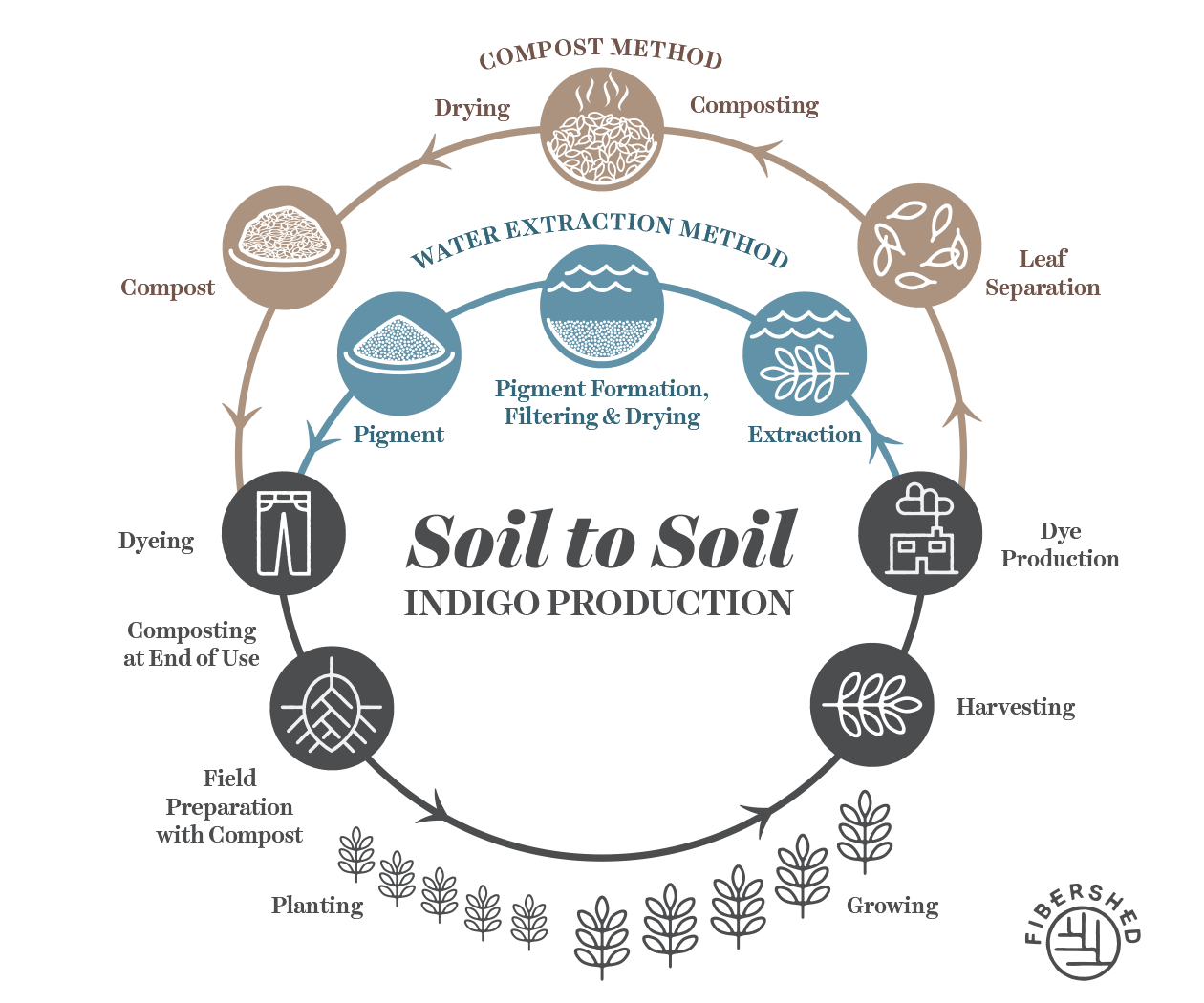

Processing Botanic Blue

Indigo is unlike most natural dyes in that it is not soluble in water; to create a usable dye the pigment must be extracted from the leaves and combined with materials that will make the color accessible to fiber. In Northern California, our approach has followed a traditional composting and fermentation process, including: 1) drying the leaves and separating them from the stems, 2) composting the leaves to break down the cellulosic material and concentrate the blue pigment, and lastly, 3) use the resulting concentrate, called sukumo, to create water-based fermentation vats. (Photo below by Kalie Cassel-Feiss) [THIS IS SAMPLE TEXT FROM FIBERSHED.COM, PLEASE REMOVE & CREATE ORIGINAL CONTENT – QUOTING FROM & LINKING TO FIBERSHED.COM IS ENCOURAGED IF YOU WISH TO SHARE CONTENT]

[THIS IS SAMPLE TEXT FROM FIBERSHED.COM, PLEASE REMOVE & CREATE ORIGINAL CONTENT – QUOTING FROM & LINKING TO FIBERSHED.COM IS ENCOURAGED IF YOU WISH TO SHARE CONTENT]

In our Northern California Fibershed we modeled our indigo processing system from what we learned from Indiana University professor Rowland Ricketts, who studied and apprenticed extensively in Japan. We learned that to make a successful fermentation vat with composted indigo (sukumo), the size of the crop (in our region of California) must meet or exceed 5,000 plants, yielding the approximately 440 pounds of dried leaf that is required to generate a robust and hot compost pile. Fibershed built a specially designed composting floor (of clay, rice hulls, sand and stone), with the hands-on support of Rowland Ricketts, a team of local designers and Nicasio Native Grass Ranch owner, John Wick. (Photo by Paige Green)

True Blue

[THIS IS SAMPLE TEXT FROM FIBERSHED.COM, PLEASE REMOVE & CREATE ORIGINAL CONTENT – QUOTING FROM & LINKING TO FIBERSHED.COM IS ENCOURAGED IF YOU WISH TO SHARE CONTENT]

The True Blue Project received support from the Jena and Michael King Foundation and was grounded in an effort to assess the economic, social and environmental efficacy of bioregional indigo production.

The project scope included field research for climate beneficial farming practice, a landscape assessment on current dye practice (synthetic & natural), and in an in-depth analysis on planting, harvesting and pigment extraction from plant-based indigo sources. The results of the research are broken into three parts that include a general overview on indigo and blue dye, a focus on planting and harvesting strategies, and lastly, water-based and compost-making pigment extraction methods. The issuance of these documents to the general public is in alignment with Fibershed’s mission to both provide open source education in natural fiber systems and to advance textile research efforts. These documents are useful for students, practitioners, rural economic development agencies, teachers, and those who are just getting involved in the subject of plant-based dyes.

Indigo: Sources, processes and possibilities for bioregional blue is Part I in a three-part series of documents that are being issued over the course of late 2017. Indigo briefly and succinctly contextualizes plant-based blue within a broad framework that includes: Sources of Blue, Chemistry of Indigo Extraction, Plant-Based Indigo, Synthetic Indigo (including Synthetic Biology), Indigo Content, Purity, Limitations, Planting, Harvesting, Extraction, and Resources for your own hands-on learning. We recommend this first document as groundwork for the reader; its aim is to lay a broad overview and foundation of plant based indigo processes within a modern context.

Indigo: Sources, processes and possibilities for bioregional blue is Part I in a three-part series of documents that are being issued over the course of late 2017. Indigo briefly and succinctly contextualizes plant-based blue within a broad framework that includes: Sources of Blue, Chemistry of Indigo Extraction, Plant-Based Indigo, Synthetic Indigo (including Synthetic Biology), Indigo Content, Purity, Limitations, Planting, Harvesting, Extraction, and Resources for your own hands-on learning. We recommend this first document as groundwork for the reader; its aim is to lay a broad overview and foundation of plant based indigo processes within a modern context.

Download the PDF: indigo-sources-processes-possibilities-june2017

Indigo Planting & Harvesting is Part II in a three-part series. This document aims to support regional farmers in their efforts to bring indigo farming forward as a viable economic option. We give a detailed review of the planting and harvesting processes in indigo dye production and consider how to scale production using appropriate tools and technology. We give equipment recommendations for a range of capital costs and for scales of operation from backyard gardens to multiple acres. The recommendations in this report are applicable to both the compost and water-extraction dye extraction processes, which are explored in detail in an upcoming report.

Indigo Planting & Harvesting is Part II in a three-part series. This document aims to support regional farmers in their efforts to bring indigo farming forward as a viable economic option. We give a detailed review of the planting and harvesting processes in indigo dye production and consider how to scale production using appropriate tools and technology. We give equipment recommendations for a range of capital costs and for scales of operation from backyard gardens to multiple acres. The recommendations in this report are applicable to both the compost and water-extraction dye extraction processes, which are explored in detail in an upcoming report.

Download the PDF: indigo-planting-harvesting-nov2017

The Production of Indigo Dye from Plants is the final report in a three-part series. This report presents a study of the technical, environmental, and economic factors involved in indigo dye production from Persicaria tinctoria, with the aim to support increased farm-scale indigo production in the Northern California fibershed and beyond. Two main approaches to dye production—compost and water extraction—are presented. The processes are discussed in detail, and particular designs are proposed and then modeled and compared on economic bases, illuminating paths forward and providing a foundation for a vision where communities are supported and clothed in part through the local production and use of natural indigo dyes.

The Production of Indigo Dye from Plants is the final report in a three-part series. This report presents a study of the technical, environmental, and economic factors involved in indigo dye production from Persicaria tinctoria, with the aim to support increased farm-scale indigo production in the Northern California fibershed and beyond. Two main approaches to dye production—compost and water extraction—are presented. The processes are discussed in detail, and particular designs are proposed and then modeled and compared on economic bases, illuminating paths forward and providing a foundation for a vision where communities are supported and clothed in part through the local production and use of natural indigo dyes.

Download the PDF: production-of-indigo-dye-dec2017

(Photo above by Kalie Cassel-Feiss)

[THIS IS SAMPLE TEXT FROM FIBERSHED.COM, PLEASE REMOVE & CREATE ORIGINAL CONTENT – QUOTING FROM & LINKING TO FIBERSHED.COM IS ENCOURAGED IF YOU WISH TO SHARE CONTENT]

Community Research and Demonstration Indigo Projects:

Kristine Vejar of A Verb for Keeping Warm in Oakland, California, tested Northern California grown sukumo and started a vat in the backyard natural dye garden of her store. In 2013 she hosted a community dye day to allow members of the public to experience the shades of locally grown blue.

In 2014, the Berkeley Art Museum presented The Possible, an interactive exhibit that included a natural dye lab, with an indigo vat using the Northern California grown and composted sukumo. Tessa Watson of Ogaard was instrumental in making and tending the vat, which was utilized by a number of Bay Area artisans and teachers, with classes attended by visitors to the museum.

Molly de Vries has had a lifelong love of indigo, which began when she purchased a vintage indigo-dyed farmer’s kasuri kimono and pant set at the age of 16. Molly’s store Ambatalia, in Mill Valley, California, is the location of her fermentation vat and indigo dyed goods.

Mary Pettis-Sarley produces a line of yarn called Twirl, made from the fiber of animals who graze her Napa Valley ranch. A portion of her yarns are dyed in Northern California grown indigo. She started with a research vat in 2015 and she is now growing her own indigo at scale, composting with other farmers, and fermenting her dye.

Michael Masterson is a designer and sewer with 25 machines that range between 50 and 75 years old. He sews all of his own shirts in limited runs and learned the art of fermentation with Northern California grown indigo during our initial research and exploratory work with designers. Michael now continues to ferment Northern California sukumo on his own successfully for his one-of-a-kind projects.

To date, four farming operations are growing Polygonum tinctorium in their integrated systems; all are organically grown, some are grown biodynamically and others are developing no-till organic methods as part of a carbon farming strategy. Together, these farmers share in the responsibility for accumulating the critical quantity of dried leaf needed for a successful compost pile. To learn more about the farming collective you can email us at hello@fibershed.com.

Our calendar lists the occurrence of volunteer days for indigo growth and processing, and our indigo report offers additional details and resources for making botanic blue a reality in your Fibershed.

(Photos above by Dustin Kahn)